Painting a Scientific Picture: Art, Brain Health, and Lived Experience

In this perspective, Atlantic Fellow Anusha Yasoda-Mohan is in conversation with artist Vincent Devine, reflecting on his immersive week at the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI)—exploring the world of brain health and dementia, and how art can bridge science and lived experience.

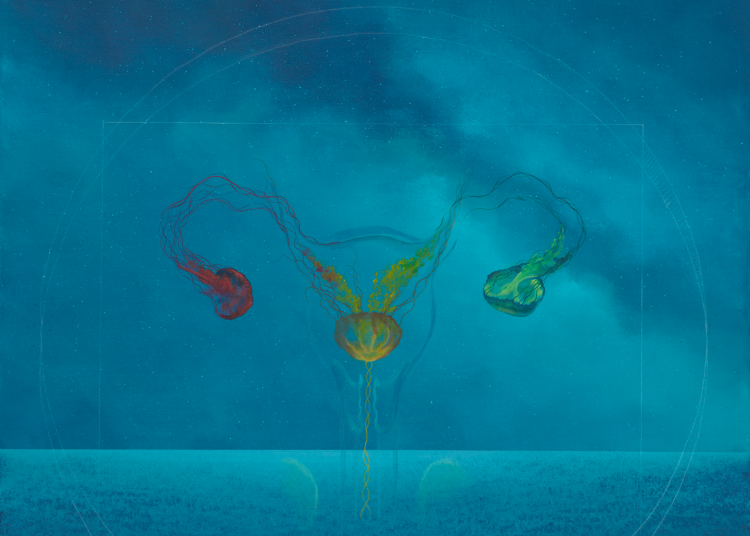

Crann Comhair by Vincent Devine. Learn more about the painting commissioned by The All Island Cancer Research Institute in Ireland.

The scientific world is rife with measurements, analyses, hypotheses and data. These form the basis for evidence-based practice, making informed choices and navigating the world with a certain intelligence.

What might our rigorous scientific world look like through an artist’s eyes? And could it move people’s hearts while maintaining its validity, arguments and evidence?

I had the privilege of exploring science communication through the visual arts with artist Vincent Devine when we welcomed him to GBHI at Trinity College Dublin as an artist in residence. Devine is a celebrated Irish artist whose work is steeped in co-creation, giving a visual voice to both the science and the lived experience of a health condition. His symbolic triptych of Vicky Phelan—a powerful advocate for cervical cancer in Ireland—and her journey through diagnosis and treatment is among his best-known works.

Anusha: Vincent, it is an immense pleasure to chat with you. How did you prepare for your time at GBHI?

Vincent: I usually go into these experiences blind, so I can have a visceral introduction to worlds I’m not used to. In cancer research, it all began with curiosity—learning about a jellyfish that fluoresces green. The same curiosity drove me here: discovering how the brain works and how neurodegenerative diseases progress. So, my preparation was to not prepare—and it turned out to be a very powerful experience.

If I’d asked you the question, “What is brain health?” before your visit to GBHI, what would you have told me?

My idea of brain health used to be simply about keeping your brain healthy and active—though I wasn’t really sure what that involved. Now, I have a plethora of answers.

What’s one thing you think can enrich brain health?

My main takeaway is that new lived experiences and enriching your environment can strengthen your brain health. Opening yourself up to new experiences, different cultures, and the vibrancy of what’s available in the world—and embracing that diversity—can fire up new pathways in the brain. Curiosity in itself is good for your brain health.

There’s a saying: “There is no health without brain health.” Why aren’t people talking about it?

I think people automatically equate the brain with the mind and don’t see it as a biological organ with weight and importance. With neurodegenerative diseases like dementia, many don’t realise that affected individuals are actually losing parts of their brain. Greater understanding of this biological reality could help foster empathy and increase awareness. There’s a stigma around dementia but knowing more about the brain’s biology would help break down those barriers.

How do you think we should talk about the brain and brain health?

By inviting the conversation in and reassuring people that everyone’s input is valuable. When someone shares their experience of dementia without judgment, it enriches our understanding of public perception. Hearing the science behind those experiences can be incredibly validating turning “I thought he was just losing his mind” into “Now I understand what was happening.” This dialogue—scientists learning from lived experience, and patients learning from science—is what science communication is about.

What concept inspired you, and how would you approach it in your work?

Cognitive reserve is my new jellyfish. Stepping outside your comfort zone to engage with new experiences creates reserve—you’re literally building new, brilliant pathways in your brain. Simply living in the world and experiencing its diversity can delay the onset of a serious condition like dementia.

Visually, I see it as a living, expanding landscape—pathways like intertwining branches glowing where new experiences spark fresh connections. Symbols or animals could travel along them, carrying memories and skills like treasures. Some areas would be dense and bright from a lifetime of curiosity; others more fragile, showing where reserve is being drawn upon. Subtle fractures would be bridged by new growth, reflecting resilience against neurodegeneration. Even in decline, there’s beauty and strength in what we’ve built over time.

Co-creation is central to my work. I start by listening—scientists bring precision, lived experience brings humanity, and together they create something richer.

— Vincent Devine, artist

And how would co-creation play a role?

Co-creation is central to my work. I start by listening—scientists bring precision, lived experience brings humanity, and together they create something richer. For a concept like cognitive reserve, I’d involve scientists, people living with dementia, and their care partners in continuous dialogue. This way, the work is a reflection of the people whose lives it touches, speaking to the head and the heart. Also a unique aspect of my practice is that the paintings are never truly finished; I can continue adding to them as new research or advancements emerge.

What was your experience of the Atlantic Fellows at GBHI?

It felt like a melting pot of brain health expertise—with space for everyone. Meeting fellows from so many different backgrounds made me feel welcome as an artist without a scientific background. That diversity of perspectives is enriching, validating, and powerful.

What was a powerful moment you will take away with you?

Shadowing Professor Leroi in the clinic, I saw a duty of care centred on the person and the caregiver. Asking questions such as “What’s the one thing you would want to change?” gives back a sense of control. Caring for the caregiver was explicit, weighing treatments against their pressures. Underpinning it all was an ethical awareness—it’s not just about treating and moving on but understanding and supporting the microenvironment around the patient and the diagnosis.

From your experience at GBHI, what message do you believe should be shared more widely with the public?

The most powerful takeaway for me is that the brain likes novelty, and also has neuroplasticity. You can enrich your brain health by seeking out new experiences beyond your usual environment. Doing so not only strengthens your neurological landscape, it also fosters empathy, understanding, and respect for diversity. That alone can improve brain health. It’s something everyone on the planet should know, and it has the potential to bring us together as a collective.

More Information

If you are interested in connecting with Vincent Devine about his work you can email him at vincent@vincentdevine.com.

The Vitruvian and The Vitruvian: Cellular by Vincent Devine. Read more about this work commissioned by UCD Conway Institute, University College Dublin.

Authors

Anusha Yasoda-Mohan, PhD

Neuroscientist

Vincent Devine

Artist